One of the most important issues in distinguishing modern art from postmodern art concerns the very process through which postmodernism emerged—a process whose beginning remains a matter of debate. Some scholars see postmodernism as a continuation of modern art, others trace its origins to the rise of Dadaism and Surrealism (themselves part of modernist transformations), while another group situates its emergence in the 1960s and 1970s.

Given that we are arguably still living within the postmodern condition, with no clear sense of its conclusion, any definitive judgment about its origins remains difficult.

By contrast, despite disagreements, modern art can be roughly located in the period following Realism and Impressionism, and alongside the emergence of movements such as Fauvism.

Another fundamental point of contrast lies in how artistic movements take shape. In the modern period, schools of art can often be understood as the result of synthesis, confrontation, or dialectical tension between paradigms within the history of thought. In this sense, one can imagine the opposition of an antithesis to a dominant paradigm—such as Realism—eventually producing a synthesis, as in the case of Impressionism, which then becomes a new paradigm or thesis. In the postmodern period, however, paradigms do not shift in this linear or dialectical way—or may not shift at all. Multiple, simultaneous, and distinct movements can coexist within a single paradigm. As a result, the rise and fall of paradigms is relatively identifiable in modern art, and the processes leading to new paradigms can be studied. In postmodern art, by contrast, we are not necessarily confronted with such clear cycles of emergence and decline.

Another distinction concerns the relationship to the past. In postmodernism, return, revival, and reappropriation of the past are defining features. In modernism, however, engagement with the past typically takes the form of confrontation, leading to the emergence of new paradigms and contributing to the forward momentum of modern art.

While modern art allows for relatively clear boundaries between artistic forms and media, postmodern art dissolves these distinctions. In the postmodern condition, we encounter media-crossing and transmedia practices, often resulting from the hybridization and synergy of different art forms. Multimedia, intermedia, and cross-disciplinary arts become increasingly prominent.

The circulation and presentation of art in the postmodern period also move away from centralized systems dominant in the modern era. Central authority gives way to multiplicity and dispersion, replaced by numerous smaller and more decentralized sites of exhibition and distribution.

Postmodern art is also marked by the visible presence of minorities, diverse gender identities, and artists from a wide range of geographical contexts. Compared to the modern period, this global and pluralistic presence is striking, enabling the expression—and reception—of dissenting voices and fostering a greater readiness to listen to them.

Unlike modern artists, who often belonged to specific schools or intellectual traditions, postmodern artists tend to embody fragmented, hybrid identities and mobile modes of thought. Artistic boundaries become blurred, and at times even disrupted, in ways that sharply contrast with the clearer categorizations of modernism.

Similarly, while modernism established distinctions between “high” art and lesser or popular forms, postmodernism destabilizes and breaks down these hierarchies.

In the postmodern era, increased attention is also paid to ecology, environmental art, and site-specific practices—areas that held no central position in modern art.

Issues of gender, identity, and racial minorities occupy a significant place in postmodern art. In modern art, these differences are more sharply demarcated and often provoke resistance, sometimes even giving rise to new aesthetic boundaries or paradigms. In postmodernism, by contrast, such concerns appear largely normalized and broadly accepted.

Postmodern art can also be described as developing without a single trunk or central body—like shoots emerging directly from the ground and taking root independently. Modern art, on the other hand, is shaped by a dominant belief system or overarching ideology, functioning as a trunk from which various movements branch out and remain conceptually connected.

Form and design hold central importance in modern art, whereas postmodern art often embraces chance, contingency, and accident in the creation of works.

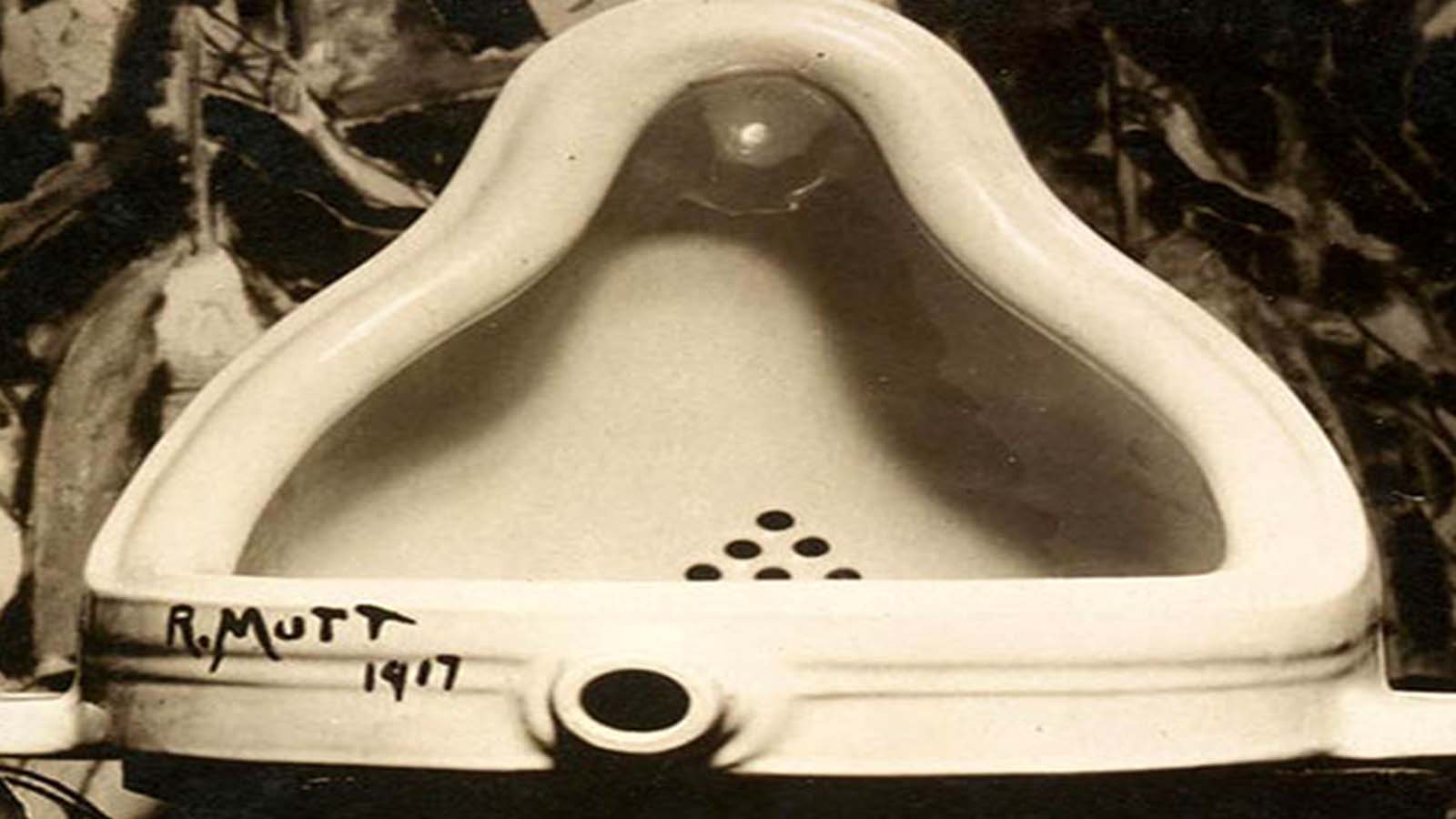

In modern art, the artist’s intention is crucial, as it is closely tied to the formation of a paradigm or dominant idea. In postmodern art, however, emphasis shifts toward process, performance, and modes of presentation.

Interpretation also takes on a different role. In postmodernism, interpretation is not aimed at recovering the artist’s intention, as in modernism. Influenced by Roland Barthes’s notion of the “death of the author,” postmodern art allows for a plurality of interpretations generated by audiences, none of which holds inherent priority over the others.

Finally, while modern art is shaped by grand narratives and overarching frameworks, postmodern art is defined by micro-narratives—fragmented, localized, and multiple stories that resist totalizing explanations.